Three Years of Logging My Inbox Count

For the last few years, I have viewed my inbox count as a barometer of my stress. When I open my inbox, these two scenarios have very different effects:

The first says, “I have at least one hundred confused priorities right now; my life is in disarray.” The second says, “be still; stillness reveals the secrets of all eternity.”1

Inbox count ≈ stress

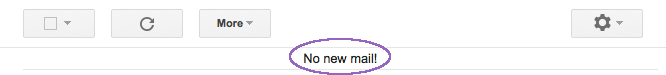

The items in my inbox represent obligations, ideas, communications, and opportunities which I need to do something about, but haven’t yet. If an email arrives and my response is, “sounds great, see you then,” I can dispatch it in a minute. Net stress: zero. However, if an email arrives that implies further research, action, or even just having to think about what a response might look like, I sometimes let it sit there. And sit there. And, as this graph of last month demonstrates, spiral out of control:

For as long as I can remember, I’ve managed my inbox via these cycles of growth and purge.

Inbox blitzes

In the “inbox zero” narrative, your inbox is like a garden. Regular tending brings gorgeous flowers; neglect brings weeds and pests. After enough neglect, things can become so overgrown that you can’t see the ground. That’s when you know it’s time to bring out the gloves, rake, shovel, and whatnot to commence an all-out INBOX BLITZ.2

Everyone has their own tolerance for mental clutter. Past that threshold, life must be put on pause just for the sake of cleaning up. In Figure 1, above, you can see that my tolerance hovered around 40 messages for the latter half of March. However, in early April, as it is wont to do, my inbox snowballed (highlighted in red). It reached 70 messages before I set aside a couple hours and dealt with it.3

Here’s a more extreme case: at the beginning of this year, I spent several days visiting home after traveling. After a first pass over my emails, my inbox count stood at 130 messages. With no plans besides seeing family, I decided I would use the time for a massive blitz to get my inbox from 130 to 0. Because I had never attempted a blitz of this scale, and inspired by time-lapse projects by others,4 I recorded it:

When I reached Inbox Zero a few days later, great relief washed over me. I had tasted nirvana.

Sure, it sounds strange that my inbox count can have the power to make me do this, but I figured that’s just because I’m a bad gardener. Sometimes I may need to grab the lawnmower and be a hero, but surely there are master bonsai gardeners out there making calm, regular snips to tend their gardens.

Tracking my inbox count

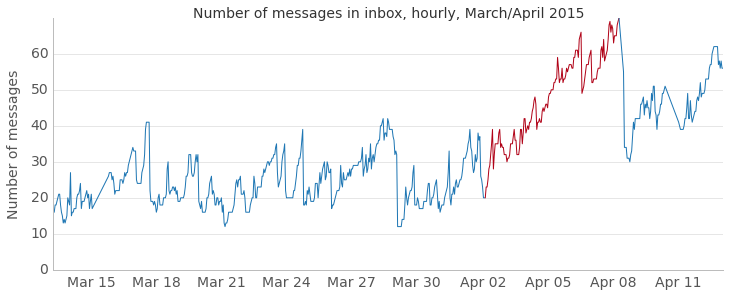

Inbox blitzes have occurred with discouraging regularity for the last three years:

This data comes from a simple script I’ve been running since 2012. It logs into my email at the end of every day and counts the number of threads in my inbox. This isn’t a summary of email content which I hope will uncover truths about my personality – great tools exist for that, and other people have already made much better attempts with their own data. Nor does it describe patterns of receiving and sending to measure how I manage email. No, these are snapshots of the magnitude of the burden I was feeling from my inbox on each day.

Keeping something in Gmail as the only way of ensuring that I’ll address it, even if it isn’t addressed until months or years later, does not exactly sound like the mark of a responsible adult. But the problem is not that blitzes happen; some form of regular purge is inevitable. The problem is my relationship to my inbox. To see why, we need to go deeper.

Email age

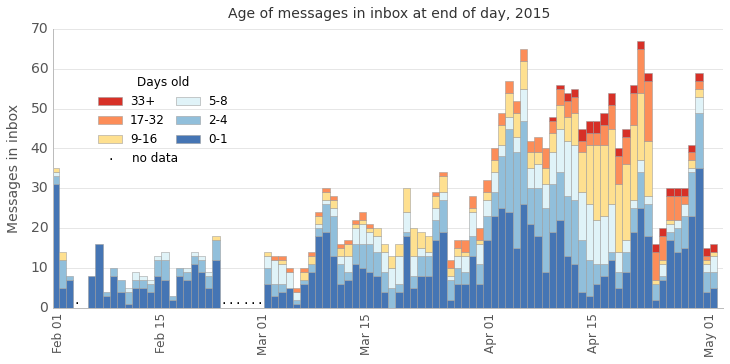

Before starting the massive inbox blitz, I began logging more than just message count: also the dates, subjects, and recipients of the threads sitting in my inbox. With this data, I can see how much of my inbox count on a given day is due to messages that I just received vs. messages that I’ve been sitting on for a long time:

The month of April illustrates the avoidant behavior which is responsible for my lifelong inbox struggle. During this period, I was a pro at staying on top of emails from the last few days (dark blue). Recent emails in my inbox hit a low point around April 15, when my inbox count was still 40+, and nearly my entire inbox consisted of old emails I was avoiding. The cache of older, unaddressed emails (yellow to orange) remained relatively stable for a couple weeks, as I continued to address more recent emails. That backlog kept the overall inbox count high for almost the entire month before I hit my breaking point and tackled them.

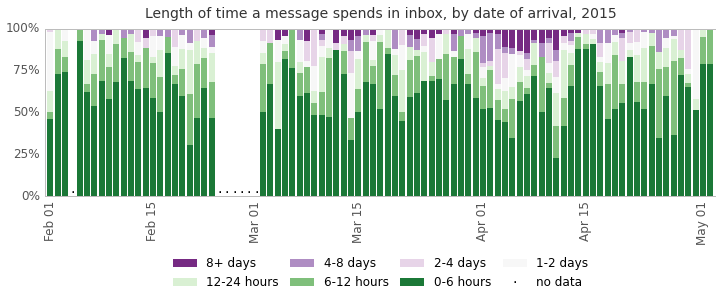

Whereas Figure 3 looks backwards at the state of my inbox on a given day, I can also look forwards starting from the time I receive an email. That is: looking at all messages that I received on a given day, how long did each email ultimately spend there before I dealt with it? The answer lies in this depressing graph:

There are some small revelations here. For example, the larger light-to-dark-purple period at the top of the graph around the first week of April indicates that around a quarter of all emails received on each of those days weren’t dealt with until at least 2 days later. That period of neglect lines up neatly with the buildup of older email that occurred several days later, towards the latter half of April, in Figure 3. But that’s not the reason this graph is depressing. This is why:

On most days – even days where my inbox count remained high – around half of the incoming messages were dealt with within 6 hours! Like a lab rat with a dopamine lever, I am addicted to the possibility of novelty that checking my email promises. After that rush comes the fleeting satisfaction of dispatching trivial emails while I am there. Meanwhile, I am repeatedly, deliberately avoiding the truly important obligations that confront me every time I am in my inbox.

Time spent checking email

It would be one thing if I were just bad at email. But I’m also great at compulsively reminding myself how bad I am at email.

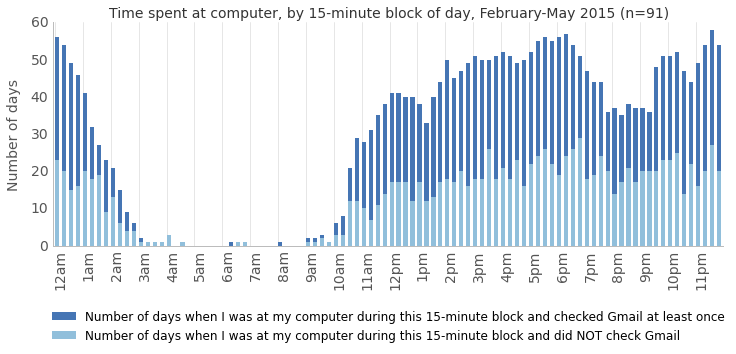

The data above comes from Time Sink, an OS X application which runs in the background and logs every time the title of the currently active window changes. Looking at the logs which correspond to the same period as the graphs above, I can see how frequently I was checking email while I was achieving the 0-6 hour latency in Figure 4.

This graph shows the shape of my average workday during these 3 months: a consistent block of activity from 10am to 7pm, often followed by more computer usage after 9pm. It also shows the sobering regularity with which I check my email: during any given 15-minute block of the day, I have only about a 50/50 chance of lasting the whole quarter-hour without reaching for a hit off the inbox pipe.

Checking email is so interwoven in my routine that I didn’t realize it had become a literal time sink. Time and attention are scarce enough as it is; I don’t need an addictive, deceptively anti-productive habit robbing me of them.

Inbox count is stress

When I started gathering this data three years ago, I saw email as a neutral burden whose maintenance can tell the story of what else is going on in my life. My only assumption was that my inbox count represents my stress. While that may be true at the extremes, the deeper discovery is that my inbox generates far more stress than it has ever represented.

To be sure, there are some shapes in my inbox rhythms which distinctly trace particular events in my life. It is satisfying to relive those stories with this concrete temporal context. But it has also been surprising, and alarming, to see the dynamics underlying those rhythms.

Whenever I stray from my task and compulsively open my inbox as in Figure 5, I am strengthening my operant conditioning. Whenever I feel a momentary rush of satisfaction from a quick pass through recent junk email, the part of me that wants to make progress on my actual priorities dies a little. When it’s possible to feel my inbox count bearing down on me like a judgment on my character, and only an overdue, dramatic purge can grant me a sense of relief, I must be doing something wrong.

I am chasing the high of inbox zero, but maybe the reason this vision of email nirvana is so enticing is that I spend so much time in a self-imposed email hell.

In The Acceleration of Addictiveness, Paul Graham suggests that as technology advances, society experiences a lag between the new addictive power of that technology and the development of customs to protect ourselves from it. As the rate of technological progress increases, so must our vigilance in building personal defenses against it:

Already someone trying to live well would seem eccentrically abstemious in most of the US… You can probably take it as a rule of thumb from now on that if people don’t think you’re weird, you’re living badly.

Most people I know have problems with Internet addiction. We’re all trying to figure out our own customs for getting free of it… It always will [seem eccentric] when you’re trying to solve problems where there are no customs yet to guide you.

Like many seemingly simple mental changes, becoming aware of a technological addiction, let alone breaking it, takes real effort to achieve. It’s a blend of deliberate, “eccentric” behaviors and environmental tweaks… including things like developing metrics that tell me whether I’m managing email or it’s managing me.

In Part 2: Outsmarting My Inbox, I explore solutions.

Graphs produced with Pandas and Matplotlib, using colors from ColorBrewer.

Get the code to log your own data and generate these graphs.

If you have thoughts on this, I would love for you to add to my inbox count.

-

Laozi, verse 16, translated by Jonathan Star. ↩

-

There is a competing school of thought which favors declaring email bankruptcy, the garden-metaphor equivalent of bulldozing your backyard whenever the weeds grow too big. ↩

-

Getting Things Done refers to this as “processing” and “organizing.” The official GTD blog claims that “most people need an hour to an hour and a half per day of total processing time to process new inputs.” ↩

-

I was initially inspired by Stan James’ amazing LifeSlice. I got more direct inspiration for the format from videos of “maniac weeks” by Bethany Soule and Nick Winter. ↩